When I think back to when I first started as an apiary technician at the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture the first thing that comes to my mind is how completely clueless I was when it came to beekeeping. I also had a lot to learn about scientific research. The more I learned the more I realized how little I actually knew. An answer to one question almost always leads to another question…

I will never forget my first day in the field at a yard just outside the small town of Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Dennis vanEngelsdorp and I met Jeff Pettis and Nathan Rice (USDA Bee Research Lab in Beltsville, MD) to take a look at beekeeper Dave Hackenbergs bees. Dave had been experiencing unexplainable colony losses and was looking to scientists to help him understand why his bees were dying. Later the losses Dave was experiencing would become known as Colony Collapse Disorder, or CCD. Anyone who has had honey bees on their radar in the last 5-7 years has heard of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and those that didn’t, might now because of the CCD phenomenon.

When we arrived at the yard, Hackenberg and his crew were pulling honey supers as Jeff and Nathan followed behind assessing colonies and taking samples. I got out of the car and Jeff yelled, “you might want to put your veil on the bees are hot”. Just as he said that I got tagged right in the forehead. “Oh man,” I thought, “this is going to be interesting”. Because I was new and had no previous experience working with bees my job for most of the day was to record notes and observe. At the end of the day I was given the chance to go through a couple of hives on my own. What a disaster! I think I made every mistake in the book that afternoon and the bees let me know it. I had been stung what felt like more than a hundred times. After it was all said and done I don’t think I lasted fifteen minutes in the car before falling asleep on the ride back to Harrisburg. I remember talking to Nathan some weeks after my initial day in the field and he told me that he didn’t think he’d ever see me again. I told him I was a glutton for punishment and liked the idea of walking into a situation that most people would go running from. Despite all the catching up I had to do I eventually learned my way around a bee hive and became competent enough to conduct disease and pest surveys in the field on my own, assessing colonies, collecting samples, and recording data.

This is my sixth year in honey bee research and honestly, right now, I couldn’t see myself doing anything else. A year ago I moved from my home state of Pennsylvania to join a team of Technicians in Northern California for an opportunity to work with sixteen bee breeders on a project known as the Bee Informed Partnership. After six years of doing field work you collect a lot of samples. A majority of those samples are of adult bees from hives to determine percent Varroa mite infestation and Nosema spore loads. Unfortunately, the way we collect, store, and process our Varroa and Nosema samples requires us to kill about three hundred bees from each hive we inspect. I’ve helped to collect thousands of Varroa and Nosema samples over the years, which equates to the deaths of millions of honey bees.

I sometimes joke around that I’ve killed way more bees than I have ever helped to save. This past year has been different though. We are out here working very closely with the sixteen beekeepers involved in our program, getting to know their operations by asking lots of questions and taking lots of samples. One of our goals is to increase colony survivorship by monitoring diseases and pests. Thanks to the team at the Bee Research Lab in Beltsville MD we are able to process the samples we collect and report back to the beekeepers with results in just under two weeks time of initial sample collection. This gives us the ability to relay information to the beekeeper fast enough for them to use it. Finally, results that are tangible and practical to the beekeepers we hope to help!

This year was full of firsts for me and one of the highlights was the opportunity to help bees in a different way…Shortly after arriving in California one of the beekeepers in our group handed our team a queen bank to have the banked queens tested for Nosema. I am happy to report that we didn’t find any Nosema and proud to say that we were able to free one queen from certain death by introducing her into a hive that was made up by using what was left of the queen bank. The hive was started in October with just three drawn out frames, a softball size cluster of bees, and a liberated queen from the bank.

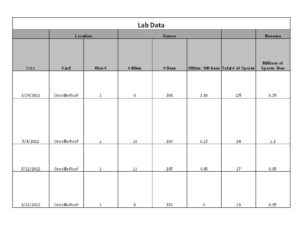

Northern California experienced an exceptionally dry and mild winter which I think played a role in the over-wintering of the colony we had slapped together. We nursed the hive through the winter and by January the bees were starting to come around. With the help of some artificial feed we were able to get the hive to the point where it was strong enough to start storing away food and producing bees. We kept an eye on the Varroa and Nosema levels by taking samples from time to time and knew that we would have to at least treat them for mites if the hive was going to become established. Below is a table that summarizes the results of our Varroa and Nosema samples.

When we started seeing mites on some of the bees and crippled wings on others we knew we couldn’t wait much longer to get a treatment in.

The star thistle is about to come on and we wanted to get the bees treated before the nectar flow began. We decided to go with Apiguard because of what we had heard about it from the beekeepers we are working with.

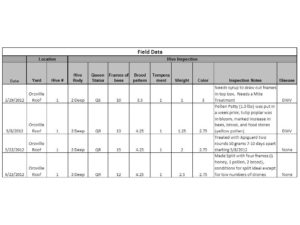

The inspection notes in the table below will tell you how and when we used Apiguard. After one round of Apiguard we saw mites decrease from 6 mites per 100 bees to 4 mites per 100 bees. Not much of a difference so we threw in a second round of Apiguard and sampled the bees again a month after the second treatment went in to the hive. The sample came up clean for Varroa! 0 mites! The treatment worked! The bees look good. They are drawing out wax, storing food, and producing brood. The bees with crippled wings have all since disappeared and upon visual inspection there are no mites to be found on adult bees.

For anyone who is interested I have also included the key that accompanies our hive inspections.

I will say that the Apiguard did slow the bees down a little. We had a couple of days where it was unusually warm for the month of May and being that the bees are on a roof the temperature rose well above the 90’s causing some damage to brood. That being said the benefits well outweighed the costs. With plenty of food available toward the end of May the bees recovered very fast and began to build again. The hive now has two deeps filled with bees, brood, and food. In fact, it looked so good that two weeks ago we decided to make a split to see if we could create another hive (see inspections notes in hive inspection table). Splitting the hive did set it back a bit but in just two weeks time it is already stronger than it was before we made the split.