Most new beekeepers find out about robbing the hard way when they either spend a little too long poking around in colonies at the wrong time of year, arrive in a bee yard already to find a frenzy of activity around hive entrances, or encounter the aftermath in the form of dead colonies and empty hives. Robbing can be particularly bad in the late summer and fall when several conditions align, leading to high potential for robbing. These triggering conditions include nectar dearth after a main flow, large colony populations with a high proportion of foragers, temperatures suitable for intense flight activity, and potential for some colonies to dwindle due to progression of Varroa or other stressors.

Once robbing in an apiary gets going, it can be hard to stop. Therefore, preventing a robbing event from getting started should be a priority. When preparing to work in an apiary at a time of year prone to robbing, beekeepers should prepare necessary equipment and materials and think through what tasks they need to accomplish in each colony prior to opening. They should then work efficiently through each colony to avoid leaving a hive open longer than necessary.

In addition to a mindset of efficiency, there are some simple practices beekeepers can follow to reduce robbing potential. Yards with fewer colonies allow the beekeeper to get in and out quicker than larger apiaries, which lessens the chances of getting colonies too stirred up. Maintaining bee-tight equipment and using entrance reducers when needed minimize the amount of space a colony has to defend from robbers. Avoiding spilled syrup or loose dripped honey in the yard will decrease the amount of robbing activity. If a beekeeper is concerned about robbing, working an apiary near the end of the day can be beneficial so the end of flying light can put an end to robbing should it begin.

Once you’ve seen a robbing frenzy in action you’ll understand how destructive it can be to a colony or an entire apiary. The last handful of bees in a weak colony may ultimately succumb to robbing, but robbing isn’t generally the primary cause of colony mortality. It is most likely that other maladies like high Varroa loads or a queen event put the colony in a state of weakness making it an easy target for other colonies. If you aren’t present to witness robbing happen, there are still some signs you can look for as a part of a postmortem.

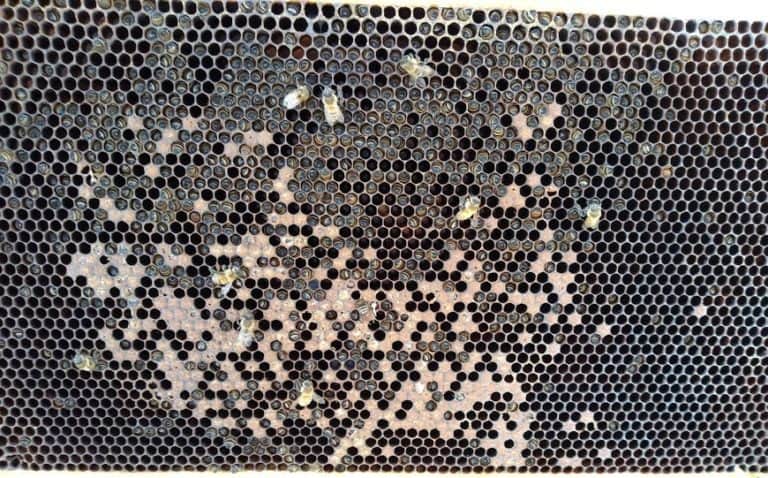

Generally when you come across a deadout it won’t have any honey in it, so you may think that the bees cause of death was starvation. But by examining some aspects of the remnants, you can determine if the colony died (or severely dwindled) with honey stores and was robbed out. By examining a deadout carefully, you may be able to learn something about how and why it died or at least eliminate some possibilities. When you find a dead colony without remaining stores, a quick post mortem to determine whether it died/dwindled with significant honey stored or perished with no remaining food stores can help point you toward a cause of mortality and lead to better informed management decisions in the future.