* This is a profile of a 2019 paper: Use of Chemical and Nonchemical Methods for the Control of Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) and the Associated Winter Colony Losses in U.S. Beekeeping Operations

The Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) Loss and Management Survey is open for your responses for the whole month of April. We would like as many beekeepers as possible to fill it in during the remainder of the month. Every year that you fill out the survey you are making a valuable contribution to science, and to our understanding of what is going on in beekeeping around the country. With that in mind, I would like to summarize a paper published in 2019 by Ariela Haber, Nathalie Steinhauer and Dennis vanEngelsdorp. It could not have been written without your responses over the past several years.

The Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) Loss and Management Survey is open for your responses for the whole month of April. We would like as many beekeepers as possible to fill it in during the remainder of the month. Every year that you fill out the survey you are making a valuable contribution to science, and to our understanding of what is going on in beekeeping around the country. With that in mind, I would like to summarize a paper published in 2019 by Ariela Haber, Nathalie Steinhauer and Dennis vanEngelsdorp. It could not have been written without your responses over the past several years.

We already know that Varroa mites are a major driver of winter colony losses through direct feeding damage to the bees, and through the viruses they transmit during feeding. Although Varroa control is an important factor in maintaining bee health, up until this point there had been no extensive study of the patterns of control measures used by US beekeepers across regions and operation sizes. This study used four years of data from the Loss and Management Survey to not only describe these patterns, but also to ask whether some Varroa control practices were associated with higher or lower losses over winter (only winter losses are considered in this paper). Furthermore, it was an opportunity to see if there were trends in treatment practices over the studied period.

Image: Nathalie Steinhauer.

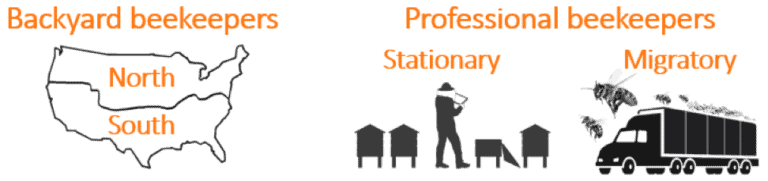

Between 2014 and 2017, almost 19,000 respondents took the questionnaire about their beekeeping. To begin to understand the data from the survey, the respondents were first grouped into small-scale (1-49 colonies) and large-scale beekeepers (50+ colonies). The small-scale group was further divided into northern and southern beekeepers, while the large-scale group was further divided into multiple-state and single-state operations. Once these divisions were made, it was possible to determine how common each practice was, and to calculate the loss rates associated with each broad category of methods. Digging deeper into specifics, the authors were even able to evaluate the loss rates associated with common constellations of individual treatments and nonchemical methods.

Photo: Dan Wyns

When grouped by their region and broad Varroa treatment strategy, different subsets of small-scale beekeepers lost between 25-60% of their colonies. Southern beekeepers and those who used Varroacides had losses lower in this range; northern beekeepers and those who used no Varroa controls or only nonchemical controls were closer to the top of the range. Different subsets of large-scale beekeepers by contrast lost between 20-40% of their colonies. These lower losses for larger operations are consistent with what we usually find in the surveys.

Large-scale multi-state beekeepers fairly commonly used oxalic acid or formic acid or thymol during the year in addition to amitraz, and those who did this tended to have lower losses (about 10-17% compared with about 22% for amitraz-only). This suggests that while it is clearly beneficial in the longer term to rotate treatments as part of resistance management, there are other reasons to rotate treatments: you may also keep more colonies alive in the short term by doing so. However, amitraz only was the most common treatment regimen for these multi-state beekeepers. I was actually surprised that so many small-scale beekeepers (of the ones who used chemical control) only used a single chemical control product. On the flip side, I was surprised how few of these used amitraz, as it is still quite an effective treatment. This study did confirm that of the beekeepers who rely on a single chemical, those who use amitraz tend to have the lowest losses.

The degree of adoption of mite-resistant stock was pretty impressive in the large-scale operations – about 1/3, a lot more than the rate of adoption among smaller beekeepers. It was associated with lower loss in the multi-state beekeepers. Splitting was another nonchemical practice that repeatedly showed up in method combinations that were linked to lower losses. This practice is highly adopted in large-scale operations, but not as much in small-scale operations – 2/3 of respondents vs. 1/4 of respondents, respectively. In terms of cultural controls, I was not surprised at the finding that only using cultural methods was linked with pretty high losses.

Like most studies, there are some limitations to how we can interpret these data. For example, the study did not investigate the timing or number of applications, dosages, or formulation. The colony and environmental conditions affect the potential benefits and drawbacks of many of your Varroa control options. So while I hope you may be able to take some clues from publications like this one, gaining a familiarity with the options and exercising judgement in selecting interventions is also essential.

As you answer the survey this year, you may be interested to think about what your winter losses were, and how your Varroa control practices compare with the ones discussed here. On the bee research side, we are certainly taking clues from your responses. By showing which Varroa control practices that in recent years have been preferred and widely used by beekeepers, your responses help provide a road map for future research on mite control.

To participate in the survey, please go here: https://beeinformed.org/take-survey/