As honey bee researcher’s photos are used to document everything from locations and landscapes to sampling events and equipment to the condition of colonies, honey bees and/or related pests and pathogens. Recently, our Northern California Tech Transfer Team used images taken in the field to help confirm the diagnosis of a European Foulbrood outbreak in an almond orchard. Some of the images I take are good; some are ok but most are bad. From my experience hundreds of pictures yield but a few images worthy of sharing.

We are currently in the process of putting together a collection of images that we hope to use for a manual that will be created to document the work we are doing as part of the Bee Informed Partnership. The manual will be produced for use as a training tool for future employees and as a guide for those looking to mimic what we do in the field and in the lab. Organizing, categorizing and assessing images is time consuming and often difficult. Many times what appears to be a terrible picture at first can sometimes end up telling a story about something completely different than what the photographer initially set out to capture. It is fun to peruse the images you have taken and imagine the picture coming to life. There have been a number of times where my images have both confirmed and denied initial interpretations and observations making them a powerful analytical instrument. Working toward the creation of our field and lab manual has forced me to go through many of the pictures I have collected but neglected to take a hard look at over the last six years.

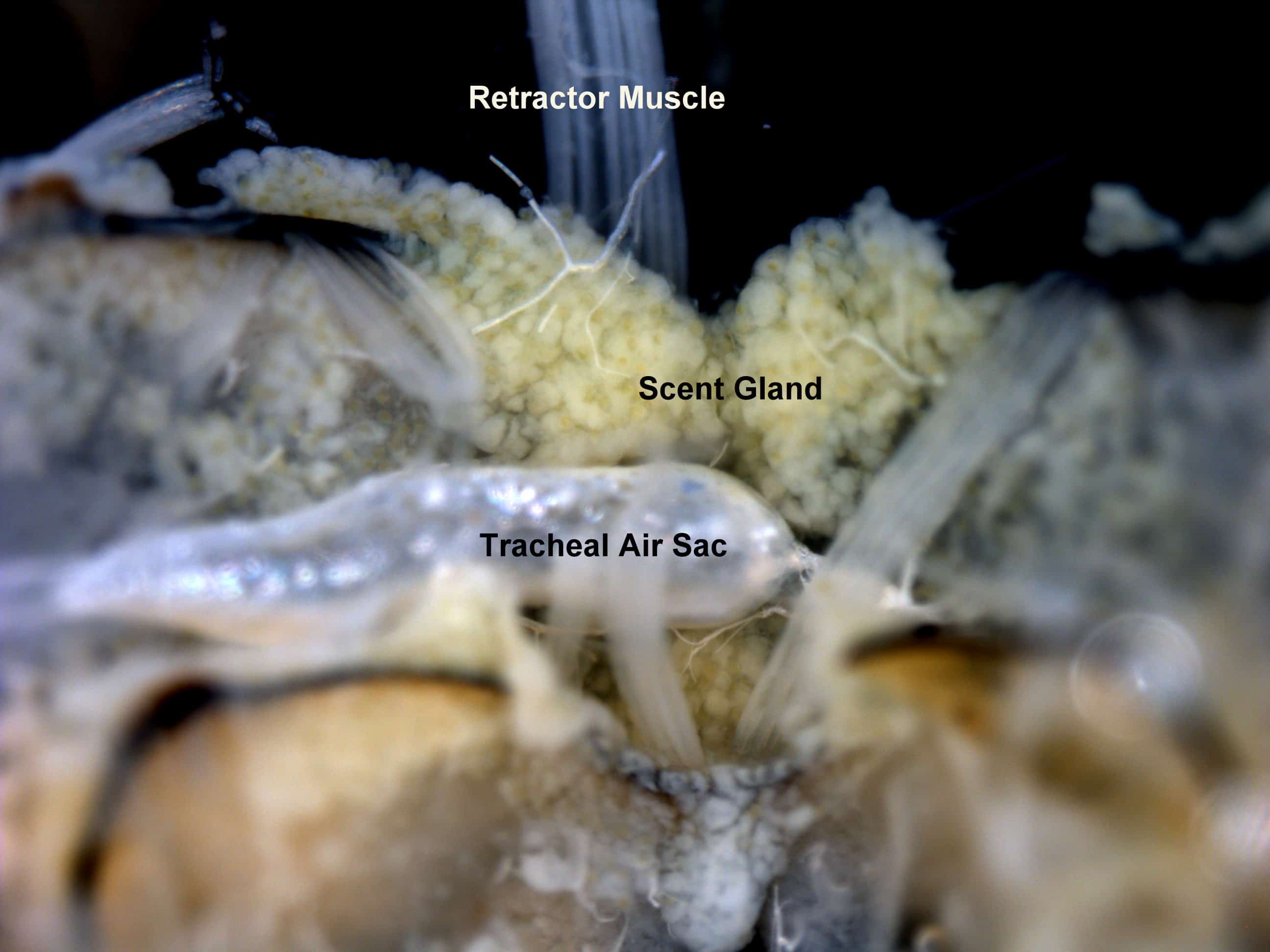

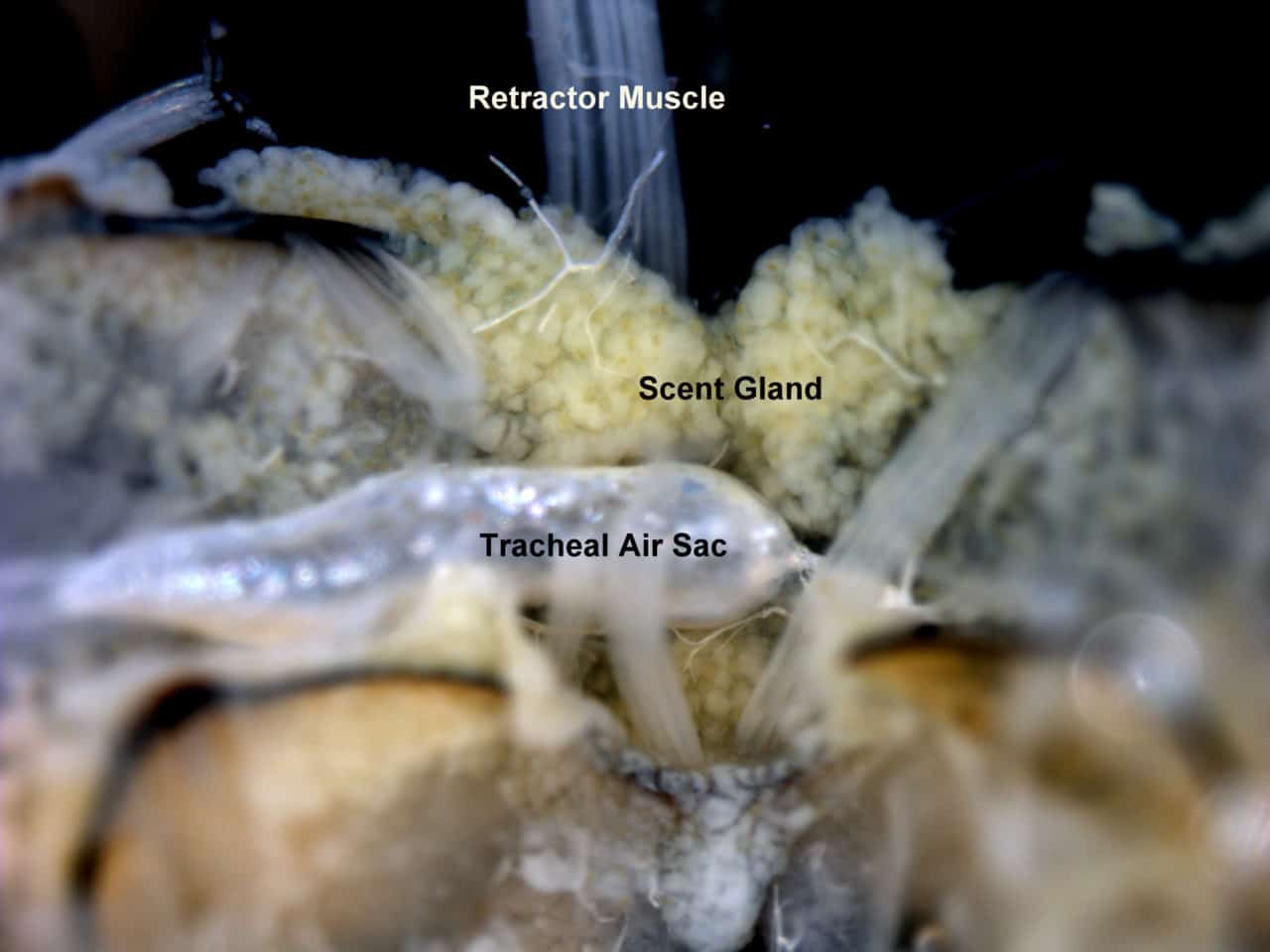

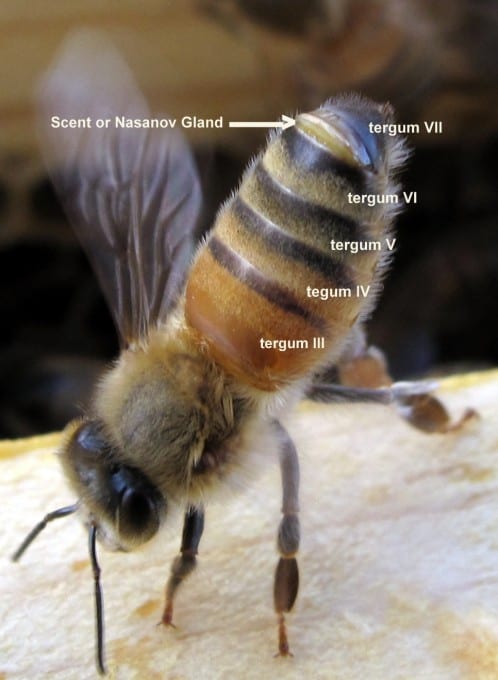

One of the finest pictures I came across was from a dissection I did during an experiment in which we were testing the effects of different storage media on the tissues of honey bees. At the time I was really into Snodgrass’s The Anatomy of a Honey Bee. I would study his drawings and then dissect bees with the goal of matching up what I was seeing under the scope with what Snodgrass had drawn in his book. I was and still am amazed at the detail of his depictions and have a profound respect and admiration for his patience, skill, and brilliance…As I got better and better at performing the dissections I began to challenge myself with dissections that would produce the opportunity to capture and exemplify the level of skill I had myself acquired through the 10’s of thousands of dissections I had completed. One of the most stimulating of those challenges was capturing images of glands because of how delicate the tissues that comprise those organs are. Sometimes I would even try to match up things I observed in the field with things I had noticed under the scope and vice-versa. One such case was that of the Scent or Nasanov gland. This gland is easily recognizable by anyone who is or has been willing to spend time observing honey bees in the field and knows when and where to look for it.

There is not a lot of information out there about the exact purpose or function of the Nasanov gland and some of what is available is contradictory. However, most would agree that gland is employed for the purposes of organization, assimilation, and orientation especially in a swarming event. One of the more interesting pieces of information I ran across was from a study done by Jacobs (1924) where the conclusion was made that scent glands, “are also present in Apis dorsata, florea, indica, adamsoni, and unicolor showing a progressive development in this order from dorsata to mellifera”. Snodgrass provides solid references of early works in The Anatomy of the Honey Bee and a simple Google search of the Nasonov Gland will produce results reviewing literature published to date. When I captured the image below I was less concerned with its function then I was with being able to dissect a bee while keeping the gland intact enough to capture an image of it (which can be just as challenging as the dissection itself). The two images identify the gland from the outside and inside of a worker honey bee.