This blog has been updated from the original blog posted on October 10, 2017. As of this date, December 12, 2017, the final paper describing the work below has been published and can by found in it’s entirety at this link at Nature.com

****************************

One of the best things about working in research is that it never fails to surprise – for good or for bad. And occasionally, it is not until much later that the surprise comes. In this case, the “surprise” arrived in the form of another Varroa-vectored, RNA virus, Varroa Destructor Virus-1, or VDV1.

Our University of Maryland lab has been leading the APHIS National Honey Bee Pest and Pathogen survey since 2010. During those years, we have processed thousands of samples from across most states for nosema spore load, Varroa load, pesticides, and viruses with the primary goal to survey whether exotics, not known to be in the US, are here or not. Secondarily, but almost as importantly, we also use the survey results to establish a nationwide honey bee health baseline. It cannot be overstated how important that baseline is, nor how vital archiving all of those samples are. In the case of viral samples, they are archived in a large -80C freezer at the USDA-ARS Beltsville Lab just down the road from us.

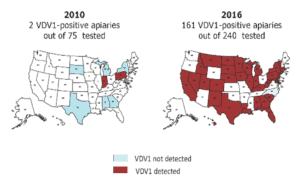

Dr. Eugene Ryabov, working at USDA-ARS with Dr. Jay Evans, decided to take a look into our archive freezer with the intent of re-processing those archived samples for VDV1. And we are glad that he did. After doing a sweep of 2016 samples, he found VDV1 in >64% of all samples, making it just less prevalent and second only to Deformed Wing Virus (currently found in ~90% of all colonies). Reaching further back into that freezer, Dr. Ryabov found that only 2 colonies were positive from our 2010 survey samples – 1 in Indiana and 1 in Pennsylvania, and that temporal snapshot [below] shows the spread of this virus in just 6 years.

VDV1 is a species of RNA viruses under the genus iflavirus. Other iflaviruses include Sacbrood virus, Slow Bee Paralysis virus and its closest relative, Deformed Wing virus. Because we have methodically stored all historic samples, it will be possible, looking at the variants of this virus in the US and the world, to possibly help resolve how and when this virus arrived on our shores. It is important to note that this virus is also present in Hawaii (the Big Island) so it has already migrated beyond the lower 48 states.

In addition to field samples, the APHIS National Survey also asks beekeepers to report colony loss numbers for the 3 months prior to being sampled. Using those losses, it may be possible to correlate those losses now with VDV1 infections and/or the levels of the virus present. This finding, and the further research it demands, provides a unique window into the forensics of this infection.

Additional information about this virus, the details used to screen for it and the possible risks to US honey bee colonies will be published in “Ryabov, E.V., Childers, A.K., Chen, Y., Madella, S., Nessa, A., vanEngelsdorp, D., Evans, J.D. (2017) Recent spread of Varroa destructor virus-1, a honey bee pathogen, in the United States. (Submitted)”.

The notice below was sent to all members of the Apiary Inspectors of America (AIA) and American Association of Professional Apiculturists (AAPA) on October 2nd.

Presence of Varroa destructor virus in the U.S.

Using RNA sequencing methods, the honey bee virus Varroa destructor virus-1 (VDV1, also known as Deformed wing virus strain B) was discovered in US honey bee samples by Dr. Eugene Ryabov, while working in the USDA-ARS Bee Research Laboratory (BRL) under the supervision of Drs. Jay Evans and Judy Chen. With guidance from the Bee Informed Partnership (University of Maryland, Dr. Dennis vanEngelsdorp) and USDA-APHIS (Dr. Robyn Rose), the BRL screened an extensive set of research samples along with U.S. bee samples collected during the USDA-APHIS National Honey Bee Disease survey. This screening confirmed that VDV was widespread in the US in 2016 and far less common in 2010. Thanks to stored samples from the National Honey Bee Disease survey, it will now be possible to track the spread of this virus in the US and guide work for virus control in order to assure the good health of honey bees and maintain them as the primary pollinator of agricultural crops. There is no indication that VDV1 is significantly more virulent than DWV in US honey bees, and the advice to reduce levels of Varroa mites remains the same for both viruses. We are seeking to inform colleagues of this discovery primarily since VDV1 is not detectable using current genetic markers for DWV, and therefore laboratory methods will need to be tailored to detect this virus. Those involved with the National Honey Bee Disease Survey will notice that VDV1 is now a reported agent in this survey.