Megachile rotundata (or the alfalfa leafcutter bee) is a species native to Eurasia that was introduced into the United States after the 1930’s because of a drop in seed production. This bee was brought into the US to increase pollination yields of Alfalfa for seed because honey bees are not the best pollinators of the crop. M. rotundata was also introduced to New Zealand (1971) and Australia (1987) for the same reasons. This solitary species is now widespread across the United States with many feral populations.

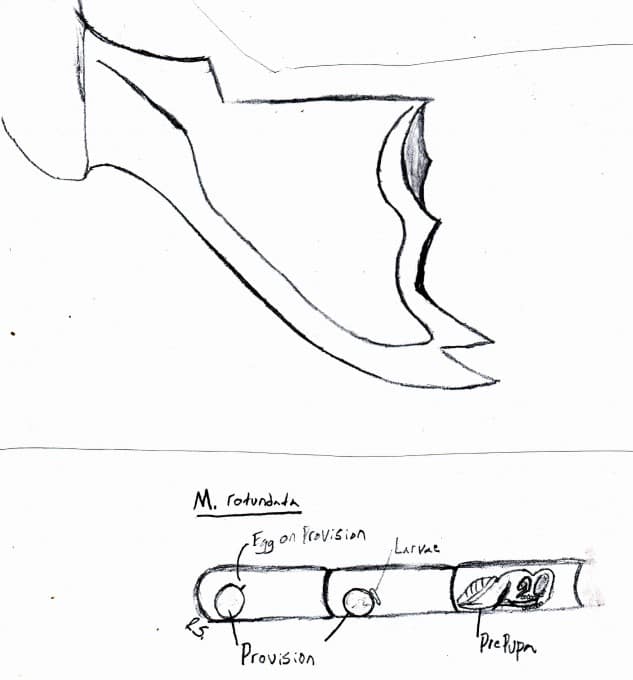

Alfalfa has a tripping mechanism that triggers the stamen (pollen reproductive organ) to strike the pollinator enabling pollen transfer to the stigma (where the pollen grain germinates). Honey bees learn to avoid the tripping mechanism and collect nectar without tripping the stamen to strike which decreases the possibility for pollen transfer. M. rotundata; however, is not as adaptable as the honey bee or it is willing to accept more abuse from the flower, taking many hits trying to collect pollen and get a taste of sweet alfalfa nectar to feed and make provisions for its young. Although the bee is preferentially oligolectic (narrow preference for pollen type) behavior, it is polylectic (opportunistic forager) collecting from various plant species if available. For commercial pollination of alfalfa, often both honey bees and M. rotundata are used to increase crop yields. M. rotundata uses its mandibles to cut oblong and circular leaf pieces to create a string of individual cells in which individuals emerge. I drew a sketch of what it would look like inside of the individual cells below as well as an image of what one side of the mandible looks like.

Normally a solitary bee, this adaptive species can be reared and kept in large next boxes containing hundreds of reproductive females (see images below). In nature this bee makes its nest in soft rotting wood, thick stemmed pithy plants, hollow reeds, radiators and even drinking straws. M. rotundata will nest in anything that is approximate to its body size.

But as you would suspect, putting a large quantity of solitary bees in overcrowded nesting sites opens the doors for opportunistic pests and pathogens. M. rotundata fall victim to three main problems: Chalkbrood, pesticide exposure and a parasitic wasp. Chalkbrood in M. rotundata is similar to that found in honey bees (Ascophera apis) but is actually a different species (A. aggregata). The parasitic wasp Ptesomalus venustus cannot reproduce without M. rotundata. The female waits until the M. rotundata larva spins its cocoon and then stings to paralyze the larva and oviposits onto the surface of the prepupa. Within 48 hours, the wasp larvae emerge and start feeding until the prepupae is almost completely gone, and then pupates itself.

M. rotundata is commercially supplied as prepupa and kept at 44-45 degrees Fahrenheit. They are then incubated at 80-81 degrees Fahrenheit for about 25 days and placed into the field (pictured below). The emerging male and female bees will soon start mating and reproducing in nearby next boxes (pictured below). I have also added images of a M. apicalis female and M. mendica male so you can differentiate the two sexes. Though they are not the same species, they are similar in size and show similar sexual dimorphism.

Even with all odds stacked against M. rotundata and honey bees, they still get the job done and pollination of the crop occurs. I have heard numbers from 2-6 colonies of honey bees per acre are needed for pollination (3 seems to be the most common). For M. rotundata 1-2 gallons per acre are needed; this depends on the amount of honey bee colonies present in the production field. 1 gallon of M. rotundata holds around 10,000 bees and is sold for approximately 85 to 100 dollars.