Varroa mites (Varroa destructor) were accidentally introduced into the U.S. in 1987 and rapidly became a destructive pest of honeybees. Not only do varroa mites suck the blood (haemolymph) of the bees, they transmit disease through this feeding and generally weaken colonies (Rosenkranz et al. 2010). Low infestations of varroa mites left without mitigation can develop into a serious problem for a hive.

It is recommended you test your honey bees for varroa mites periodically throughout the season. Here in Minnesota, we test for varroa in spring (May), in late August or early September, and then after treatment has been on for the recommended time, sometime in September. It is important to understand all aspects of your colonies so you can make informed decisions about treatment/intervention, but also so you know what might be causing problems in your hives.

There are a number of things to look for that indicate a hive is VERY infested with mites. The BIP Tech Teams pay special attention to these things when assessing colonies. They are Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) (Fig. 1) , Parasitic Mite Syndrome (PMS) (Fig.2), and very small bees.

Powdered sugar tests are simple, give immediate results, and are inexpensive to administer. The bees get coated in powdered sugar, the mites fall off because they cannot hold on to the adult bee coated in slippery powder, and then the bees are returned to their hive to be cleaned by their sisters. Also, the test is done in the field, so you don’t have a bunch of samples to assess later, and you are able to take action right away if necessary.

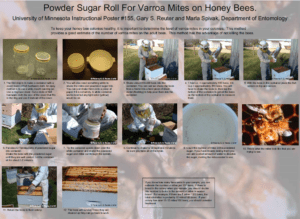

Gary Reuter and Marla Spivak, at the U of MN, have a free-to-download, easy-to-follow sheet on how to administer a powder sugar test to measure mite levels. (found on the UMN Mitecheck Webpage,) A sample of ~300 bees is dislodged from a brood frame, covered in powdered sugar, shaken into a white container, and the number of mites per 100 bees is found (If 300 bees, divide the number of mites by 3) (Lee et al. 2010).

The simple equipment for the powdered sugar test include:

- quart or pint canning jar with a ring lid (or something similar)

- 8×8 hardware cloth mesh circle

- powdered sugar

- a white bowl or bucket

- optional: a piece of metal flashing long enough to catch any bees you shake from a frame

It is important to keep good notes on your hive health, your mite numbers, and the actions you take in your colonies. You will be able to get a better picture of the health of your bees if you are able to track what is happening over time.

If a hive dies and gets robbed out, the mites (and diseases such as AFB and chalkbrood) can be transferred to robber bees which can then transfer the mites to the robbers’ colonies. Mites are also transferred through honeybee drift, where bees from one hive end up in a neighboring hive. (Frey and Rosenkranz 2014)

Consider signing up for Bee Informed Partnership’s Survey to share your results and see what’s happening with the bees through out the U.S.

Click on this icon at the top right of this page to sign up:

References:

*Frey, E., & Rosenkranz, P. (2014). Autumn Invasion Rates of Varroa destructor (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) Into Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Colonies and the Resulting Increase in Mite Populations. Journal of Economic Entomology, 107, 508–515. doi:10.1603/EC13381

*Lee, K. V, Moon, R. D., Burkness, E. C., Hutchison, W. D., & Spivak, M. (2010). Practical sampling plans for Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies and apiaries. Journal of Economic Entomology, 103, 1039–1050. doi:10.1603/EC10037

*Reuter, Gary and Marla Spivak, “Powdered sugar roll for Varroa mites on Honey bees”, (link: http://www.beelab.umn.edu/prod/groups/cfans/@pub/@cfans/@bees/documents/asset/cfans_asset_317466.pdf)

*Rosenkranz, P., Aumeier, P., & Ziegelmann, B. (2010). Biology and control of Varroa destructor. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 103, S96–S119. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.016