The National Honey Bee Disease Survey investigates honey bee apiaries throughout the US to see if three exotic honey bee pests are still absent from our shores. Samples collected from 41 states and two territories reveal that we are still free of the Tropilaelaps mite, Slow bee paralysis virus, and the Asian honey bee Apis cerana. If you think varroa is tough to manage, its diminutive cousin Tropilaelaps can reproduce much faster, resulting in many more mites feeding on developing honey bee larvae. We don’t want any of these three exotics as they would add additional stress and pressure to honey bee health. Make a call to the pest control seattle who are capable of handling this issue efficiently.

While sampling for these exotics, we used the opportunity to collect additional data on the health of honey bees nationwide. We sampled for varroa, nosema and a suite of honey bee viruses. Here we report on the varroa and nosema results.

Varroa

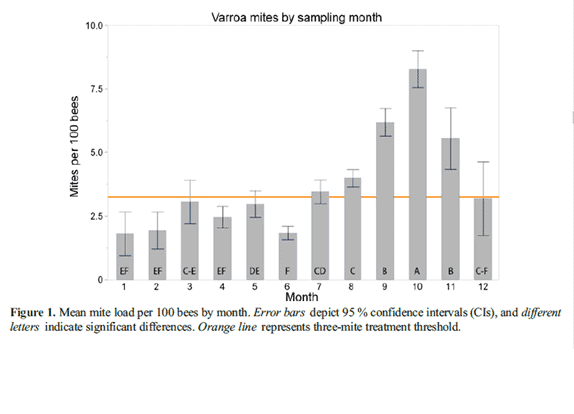

Varroa levels typically peak in late summer and early fall, when the average infestation rate nationwide rises above the treatment threshold. This means too many colonies are entering the winter with a high parasite load, making it more difficult for them to survive the winter.

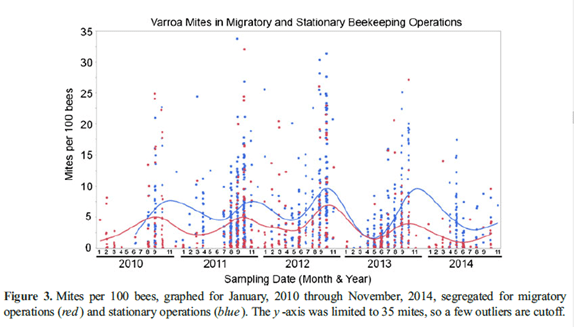

Migratory beekeepers receive a lot of flak for the poor health of their colonies. But the data tells a more complex story. Migratory beekeepers are much more successful than stationary beekeepers at managing their varroa populations. Throughout the survey, migratory beekeepers have significantly fewer varroa mites. They’re either doing a better job of treating for varroa, or the physical movement of their colonies may be reducing the mite’s ability to reproduce.

(In the figure, each dot represents the varroa load of a sampled apiary. Migratory beekeepers are in red, while stationary beekeepers are in blue. The solid line depicts the average trend for each type of operation. Every year, the varroa levels rise in the late summer and early fall, but they rise more steeply for stationary beekeepers.)

Nosema

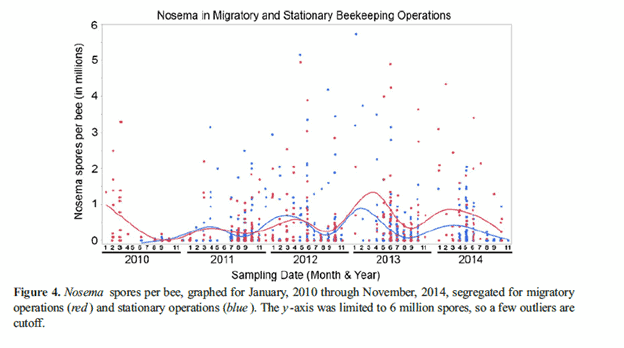

In all samples, nosema—a gut parasite that can give bees dysentery—peaks in late winter and early spring, when colonies often start intensive brood rearing. While migratory beekeepers are better at maintaining their varroa, their colonies typically have higher levels of nosema than stationary beekeepers. But despite elevated levels, the average almost never exceeds the recommended treatment threshold of 1 million spores per bee.

Viruses

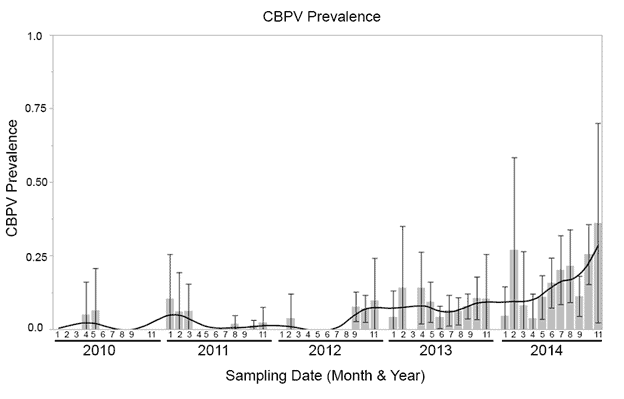

We sampled for a suite of honey bee viruses to track how they change over time. The results suggest an escalation in prevalence of several viruses over the last 5 years. Black queen cell virus, Chronic bee paralysis virus (CPBV), Kashmir bee virus (KBV), and Lake Sinai virus-II (LSV-2) were found in increasingly more samples in later years. Undetected in 2009, the prevalence of CBPV has doubled annually, a worrisome trend in light of all the other stressors impacting honey bee health.

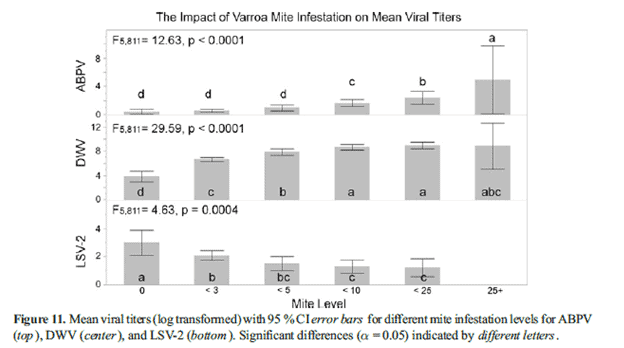

Varroa & Viruses

Varroa acts like a dirty hypodermic needle and helps to transmit viruses. The more mites in a colony, the more infected the bees tend to be. Viruses just want to reproduce. They infect a host and then start reproducing using the host’s genetic machinery. So to determine which bees were most infected, we looked at how many copies of the virus the bees carried. The number of viral copies of Deformed wing virus (DWV) and Acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV) were closely linked to the mite infestation level. The more varroa, the more viral copies we found. Only LSV-2 showed the opposite relationship, decreasing as varroa levels increased.

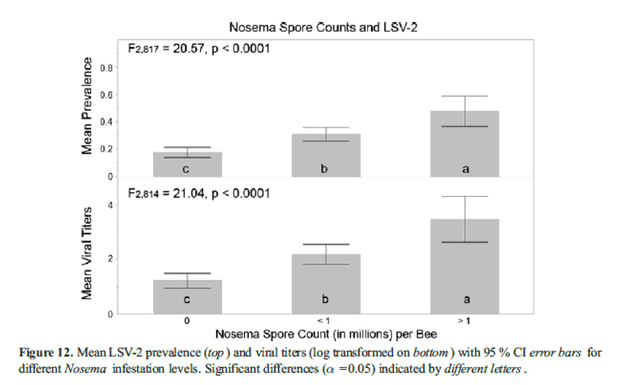

Nosema & Viruses

While LSV-2 levels had a negative relationship with varroa mite infestation, this virus closely tracked rates of nosema infection. The more nosema spores in a colony sample, the more viral copies we founds of LSV-2.

A Baseline for the Future

It’s hard to know if colony health is improving or worsening, if we don’t have a starting point with which we can compare future samples. The five year survey confirmed the absence of three exotic pests and established a baseline of disease. Such longitudinal surveys offer a rare look at seasonal and yearly patterns of parasites and viruses that threaten honey bee health. Results from such surveys can help identify the causes of poor honey bee health and provide warning signs of emergent threats. An increasing trend in multiple viruses and parasites may suggest a compromised honey bee immune system, unable to protect itself well against a wide multitude of stressors such as a fragmented agricultural landscape, increased pressure from pesticides, and poor nutrition, leading to increased colony mortality.