Working bees in November in Hawai’i? YES, PLEASE! BIP Tech Team Field Specialist Ben Sallmann and I pounced on the opportunity to leave Minnesota and Michigan’s dreary November weather. We tackled all of the logistical challenges and hopped on a plane to Hawai’i to conduct fieldwork for the state’s contribution to the National Honey Bee Disease Survey (NHBS) .

National Honey Bee Disease Survey

The National Honey Bee Disease Survey (NHBS) is a federally-funded, nationwide, annual honey bee survey. This survey has been conducted since 2010 and is a joint effort between the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and the University of Maryland Honey Bee Lab, with the support of the Apiary Inspectors of America (AIA). Survey participation is voluntary, with approximately 40 states currently participating. Most NHBS field sampling is performed by AIA inspectors, but some states require additional field support, and are sampled either by other extension offices, or by BIP’s Tech Transfer Team. In 2021, BIP performed NHBS field support in five states: California, Colorado, Louisiana, North Dakota, and for the first time – Hawai’i!

Hawai’i Honey Bee History

In 1851, the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society appointed a committee to bring the first honey bees to Hawai’i. It is a long journey to Hawai’i, and after multiple failed attempts to ship honey bee colonies on container ships to the island, the first successful shipment of 3 hives of German dark bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) arrived in Honolulu, O’ahu, October 1857. The German bees adapted well to the ‘Gathering Island’ (who wouldn’t!) and spread to all of the islands. This German bee origin bit becomes important further in this story. Later, in 1880, Italian bees (Apis mellifera liguistica) also arrived on the island. (Roddy & Arita-Tsutsumi, 1997).

Following introduction, honey bees spread across the land mostly as feral colonies, with the exception of a few colonies maintained by hobby beekeepers. It is only later in the 1890’s that managed beekeeping grew in response to the state’s large-scale cultivation of Mesquite (locally known as Kiawe) to feed the growing number of cattle on the islands. Surprisingly, sugarcane cultivation also boosted beekeeping activities; the accidental introduction of the sugarcane leafhopper, a pest of sugarcane that excretes sugary sweet droppings, or “honeydew” that honey bees will readily consume. (Roddy & Arita-Tsutsumi, 1997)

The first honey bee quarantine program on the islands started in 1908, and by 1909 they imposed a ban on packaged bee importation, in an attempt to prevent the spread of foulbrood from California colonies. They were still importing queens, but destroyed the cages they came in after introduction. The plot thickened with the arrival of Varroa on O’ahu and the Big Island in 2008, which was soon followed in by Small Hive Beetles (SHB), which by 2010 was detected on all the islands. These back-to-back introductions had devastating effects on beekeeping activities in parts of Hawai’i. Since then, there has been a full ban on importing bees, equipment, or any related product to the islands of Kauai and Maui, with the exception of semen, which doesn’t seem to be a popular practice. As a result, the islands of Kauai and Maui are Varroa-free to this day!

Logistical trip planning

Restrictions

If you think COVID-19 restrictions and travel requirements are difficult to navigate, try adding biosecurity regulations for your clothes and equipment on top of that. We had to fill out the online Hawai’i travel requirement forms, send proof of vaccination and wait for a QR code to enter the islands. In addition, we couldn’t bring any beekeeping equipment. So, we quickly decided to ship new sampling materials needed to the first beekeeper we would sample on each island and beg them to lend us some protective gear, a hive tool, and a smoker.

Itinerary

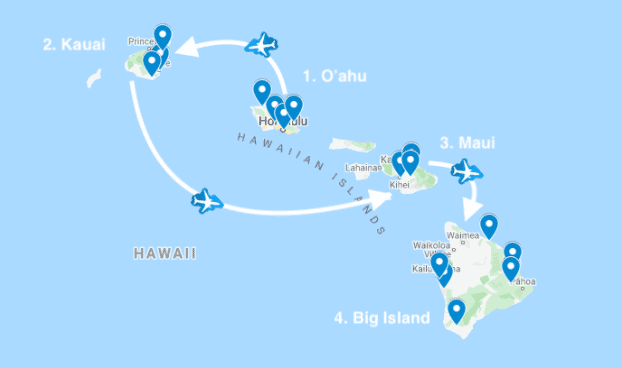

This was the first trip to Hawai’i for both of us, so we had no idea which island was which and where they were. We had a list of prior Hawai’i APHIS survey participants and that was it. So, I used Google Maps, sent a bunch of emails and made tons of phone calls. After I received a few responses, I started drafting a potential trip schedule progressing through the islands in the most efficient way I could think of. We would start in O’ahu, fly to Kauai, then to Maui and finish on the Big Island. Inter-island flights with Hawaiian Airlines are reasonably priced and extremely efficient. Lodging prices on the islands are exorbitant, and reserving rental vehicles proved difficult (and though we tried to get car transport quote, it proved to be too pricey for the trip), with shortages in some locations. So, we took a few risks and used Airbnb and Turo (a car rental app. similar to Airbnb for cars), which all worked out well in the end.

The Aloha Spirit

O’ahu

After weeks of careful planning, checking the cost of shipping a car, emails and phone calls to beekeepers, online bookings of every flavor and long shipping and packing lists, Ben and I met in Honolulu to be greeted by the Aloha spirit and our first of many rainbows.

Honolulu is a big city and not so different from other big cities, but its surrounding mountains, low clouds and mist rolling in makes for a unique backdrop. We stayed in the city, but ventured up and over the mountains the next day to visit a sideliner beekeeper on the east side of the island, an education apiary and garden center on the outskirts of the big city, and a hobby beekeeper on the northwest side of O’ahu.

Working the bees in O’ahu wasn’t much different than working bees on the continent. Ben and I quickly adopted our rhythm, me in the role of assistant to prepare all the sampling containers, fill out the forms, enter data in our mobile application and set equipment up for Ben. Ben, the true expert, was opening colonies, performing inspections and collecting samples.

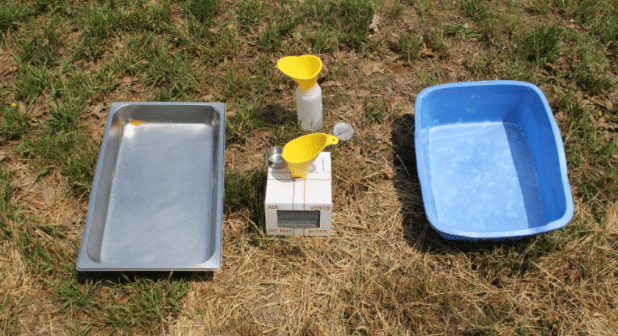

During an APHIS-NHBS sampling visit we record queen status and signs of diseases, collect bee samples that are shipped to the lab for quantifying Varroa and Nosema loads, as well as ship live bees that are tested for the prevalence and load of nine harmful bee viruses. We also collect bee bread samples that are analyzed for ~200 different pesticides, and perform a brood frame bump test to monitor for Tropilaelaps, a honey bee pest that (fortunately) has not yet invaded US colonies. When BIP Tech Transfer Team performs these sampling events, we record additional equipment information (e.g., number of honey supers), colony size (measured as the number of frames of bees, “FOB”) and perform alcohol washes for immediate Varroa load estimates.

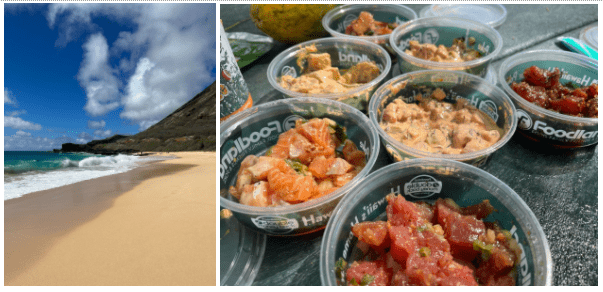

The drive between apiaries gave us a chance to admire the beautifully diverse coast line and visit Koko Crater Botanical Garden. There was so much more to experience on O’ahu and we regretted not taking an extra day to explore this island, but alas, we flew out the next morning.

Kauai

I had a lot of romantic notions about Kauai. In my many dreams prior to our trip, I envisioned it as a most comfortable tropical paradise, where we would work pleasantly gentle Varroa-free bees. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Kauai is called the ‘Garden Island’ and is considered to be the most ‘wild’ and pristine of all the Hawaiian islands. With its big, ridged mountains, low clouds and mist all around, the island is majestic – ominous and austere all at once. Kauai is also pretty wet and muddy in November.

Perhaps this misty, solemn atmosphere taints the bees’ demeanor in Kauai, because let me tell you – working bees in Kauai was a different experience. The majority of the Kauai bees we visited were ‘spirited’ to say the least, and the use of smoke only served to further agitate them. I have never seen Ben work so efficiently! Some think their pugnacious demeanor is caused by the reduced genetic diversity resulting from the island’s strict import restrictions, allowing the resurfacing of traits that expose their dark German origins (I told you that bit would make a comeback). Whatever the case may be, Ben and I did not linger with Kauai Varroa-free bees because we found them a bit unpleasant to work with, to put it mildly… On the other hand, the bees’ demeanor was offset by the generosity of the Kauai beekeepers. We returned to our Airbnb that night with Kauai honey, raw macadamia nuts, ripe avocados, longans and rambutans we plucked from the trees surrounding the apiaries. We were thankful for the sustenance, because working those bees was exhausting.

We had a chance to explore Kauai the following day. We focused on the North East side of the island. We got some beach and snorkeling time, explored Hanalei bay and got in a slippery and muddy hike just before nightfall. I vowed to return to Kauai to explore the West side of the island and to hike the Napali trail.

Maui

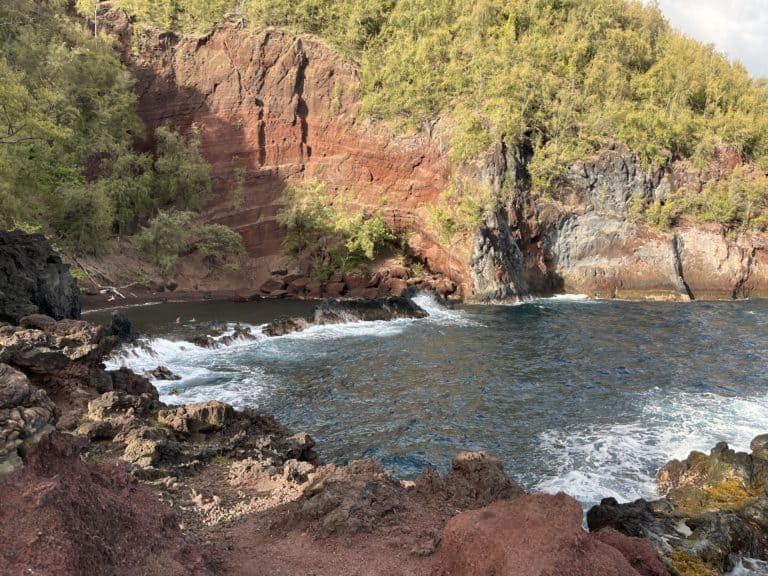

Maui is famous for its beautiful beaches and our Airbnb across the street from Charlie Young beach did not disappoint. But Maui, also known as the ‘Valley Isle’ is so much more. Dry on the West side and wet on the East side, Maui offers booming agriculture, sacred grounds, waterfalls, and one of the most harrowing drives I have ever been on. Dubbed ‘the road to divorce’, I can say that I (we) survived the Road to Hana, thanks to Ben’s driving prowess.

Despite the adrenaline rush from driving the road to Hana, Maui has the most laid back feel of all the islands. This ‘hang loose’ attitude was true of the beekeepers we visited on the island. One beekeeper set up shop with an Artist and works in a collaborative creative gathering space, while another tends his beekeeping business on a farm producing more crops than we could count, and a little home market complete with baked and prepared goods, and a pollinator education center.

Like Kauai, the bees on Maui are also Varroa-free, and also had assertive tendencies. Perhaps we were more prepared, or maybe because they were part of larger beekeeping operations, we felt they were a slight improvement from the previous island. Both Kauai and Maui beekeepers are most concerned about small hive beetles (SHB), which they see as the biggest threat to their bees. We did see some SHB, but nothing more concerning than on the mainland.

In Maui, we were gifted Kiawe (mesquite) and winterberry (Brazilian pepper) honeys, both different than other mesquite and Brazilian pepper honeys I have tasted in the past. I really enjoyed chill Maui.

Hawai’i – The Big Island

As the name implies, the Big Island is the biggest of all the Hawaiian islands, and from that fact alone I came to with some sweeping general assumptions. In my mind, I anticipated the Big Island was going to be big, touristy and commercial. I was mostly excited about the queen producers we were going to meet. Ben, on the other hand, was really excited about the Big Island, so who was I to crush his enthusiasm? Perhaps his sense of wonder rubbed off on me, and mostly because I was so wrong about the Big Island, I was enchanted. This island of volcanoes, beaches of every sand color, places desolate from old lava flows and others lush and tropical was buzzing with bees, beautiful scenery and unique experiences.

We drove straight from the airport to one of the major queen producers on the island. Wearing only a very optional veil, we were enveloped in hot, humid, heavy air with bees just clinging to us, seeming to greet us with the true aloha spirit. It was the most meditative and magical experience I have ever had with bees. I swear if the operation owner had asked me to come work for him, I would have said yes on the spot, but he didn’t…

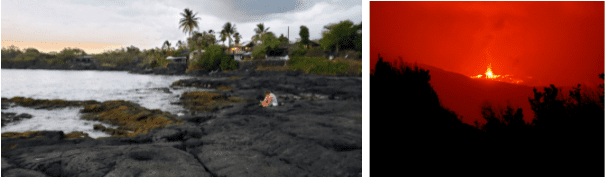

Our days on the Big Island consisted of beautiful scenic drives to one part of the island or another, a sampling visit to a beekeeper or two, a stop at a black, green or red sand beach and/or an island natural attraction, rinse and repeat. We visited two other major queen breeders on the island, sampled bees sitting on a hardened lava flow, visited a queen breeding bee lab, and sampled some specialty honeys from a USDA certified organic honey producing outfit. Bees and beekeepers alike were, not surprisingly, welcoming and fascinating.

Some days we barely made it to the beach in time for the sunset; others, while Ben was refreshing himself in the sea after sweating in the bee yard all day, I sat on the beach, sending reports or contacting beekeepers we planned to meet the following day. I am certainly not complaining here, as we managed to pack in as much fun as we could during our 5-day stay on the Big Island. We hiked to the Captain Cook monument and snorkeled at Two Step, visited the most enchanting tropical botanical garden, stayed in a few scenic Airbnbs, lulled to sleep by the charmingly loud coqui frogs, and did a 5-mile night hike to see the erupting Kilauea lava flow.

I think the most surprising and refreshing aspect of Hawai’i for me was that none of the islands we visited were overdeveloped the way many tropical destinations are. Hawai’i is still filled with what I can only describe as a natural rawness. Overall, the first BIP Hawai’i APHIS NHBS sampling trip was a success. We sampled 120 colonies from 15 beekeepers during our 12-day stay. We took 10 flights, drove over 1,000 miles all around four Hawaiian islands and brought back innumerable memories.

References

Roddy, K. & Arita-Tsutsumi, L. (1997), A history of honey bees in the Hawaiian islands, J. Hawaiian Pacific Agriculture Journal 8:59-70

Authors: Anne Marie Fauvel & Ben Sallmann, BIP Tech Transfer Team