Collaborations That Give Back – Featuring Dr. Katie Lee

Authors: Rachel Kuipers and Eric Malcolm

BIP is frequently contacted by beekeepers across the country who have experienced what we suspect are mite-related losses, not realizing their mite loads throughout the course of the season. Recent findings indicate that even those maintaining the commonly suggested 3% action threshold may still lose colonies to mite-related issues.

Previously, industry standard for the Varroa action threshold—the threshold at which beekeepers should take action against the mites to avoid mite-related damage to their colonies—was a 3% infestation rate or higher throughout the season. The damage threshold, or the point at which mite damage becomes observable and may become difficult or even impossible to successfully reverse, was generally considered to be the same 3% rate.

Dr. Katie Lee started working with Bee Informed Partnership as a founding member of the BIP Tech Transfer Team in the Midwest region in 2012, serving commercial beekeepers across North Dakota as what is now referred to as a field specialist. She went on to earn her doctorate under Dr. Marla Spivak at the University of Minnesota.

However, in recent years, further research has shown that not only does the action threshold vary throughout the season, but it may actually be lower than previously believed.

In 2017, a research study conducted by Lee for her doctorate used BIP data and protocols to conclude that the spring action threshold is actually closer to 1%. Lee, now an extension associate at the University of Minnesota, also currently serves on the BIP Board of Directors.

From May 2012 to Mar. 2017, Lee inspected and sampled commercial beekeepers’ migratory colonies. The colonies started the year in North Dakota or Minnesota, moved to California for almond pollination, and then moved to Texas, Mississippi, or Louisiana before eventually returning to the Upper Midwest. During the project, Lee sampled about 40 colonies—10 colonies each across four locations—per beekeeper four times, following the same colonies as much as possible. Colonies were inspected and sampled first at the start of the beekeeping season in May or June, right after the first treatment, then in August after supers were pulled, then September or October to see how effective fall treatments were, and finally once the bees went to California for almond pollination in winter or to the deep south for queen production. The inspections included key colony metrics, such as frames of bees, brood pattern, and visible signs of disease.

The largest observation was how much mite loads affected operation losses. This wasn’t unexpected, Lee said, but the surprising part was how clear the relationship was.

From spring to summer and summer to fall, odds are that if your mite counts start high they will end up higher.

Colonies that started in the spring with 1-2 mites per 100 bees or ≥2 mites per 100 bees had 3.5 and 6.5 times higher odds, respectively, of having ≥3 mites per 100 bees in the summer than colonies that started with fewer than 1 mite per 100 bees. Colonies with 1-3 mites per 100 bees in summer, however, had 7.2 higher odds of having ≥3 mites per 100 bees by fall than colonies with 0-1 mites per 100 bees. To calculate the odds, Lee used the odds ratio—a measure that calculates the strength of association between two events—and took into account year-to-year and operation-to-operation variation. To read more about her results, you can access her paper here.

The risk with prolonged exposure to higher mite counts is that the viruses transmitted by Varroa to honey bees and then between honey bees within a colony rapidly increase and continue to negatively impact colony health. The longer a colony is exposed to high mite loads and mite-related viruses, the weaker the bees are going into winter.

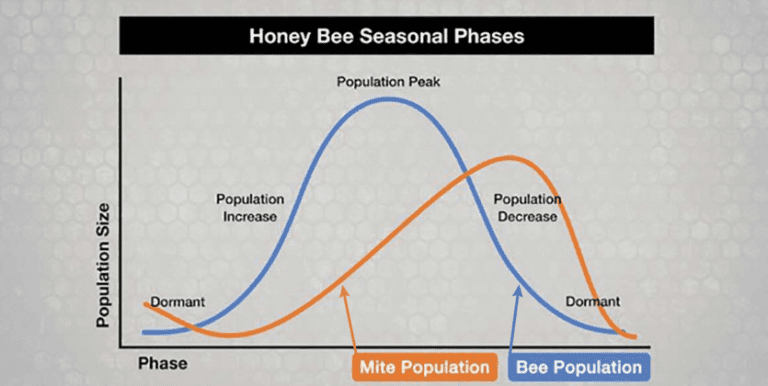

Another reason it’s important to take control of mites in the spring is because of the variance in honey bee and mite populations throughout the season.

As honey bee populations increase throughout the season, the mite populations typically are not far behind. For example, if a colony has 20,000 honey bees and 1,200 mites in the spring and maintains the same infestation rate throughout the season, around the time it expands to 50,000 bees the mite population would explode to 3,000—a much more difficult number of mites to manage. Mite populations also decrease after honey bee populations do in the fall, leading to potentially sharp increases in Varroa infestation rates.

Colonies also tend to become larger and heavier as the season progresses, factors which make treating effectively more difficult.

So, what advice does Lee have for beekeepers?

Monitor: “The more colonies you sample, the better idea [you have] of what the mite levels are like at that location.”

And get a handle on mite loads early in the season: “[I] recommend that everyone manage mites in the spring to keep mite level from getting too high in the summer,” Lee said.

This past August, the Honey Bee Health Coalition published the 2022 edition of Tools for Varroa Management, which also highlights revised suggested action thresholds for managing Varroa loads in your colonies. We highly recommend checking it out!