If you are an almond grower, a beekeeper or simply live in Northern California, you know where to find most of America’s honey bee colonies in late January through February. Close to two million honey bee colonies come from all over the United States to pollinate the almond blooms each year. But then what? If getting bees to California is like a sprint for beekeepers, what happens after is more like a marathon. When the last almond petals fall, the beekeepers’ most intensive work period begins.

Lightning Speed Honey Bee Biology and their Life Cycle

In nature, honey bees reproduce on two levels. At the individual level, honey bee queens lay eggs that will be raised to adulthood to grow the colony population as a whole. And at the colony level, when the population outgrows their home, the colony divides and swarms, leaving the nest behind with resources for the remaining workers to make themselves a new queen. This swarming process results in two colonies or more.

The ultimate goal for honey bees, as for all living organisms, is to reproduce. On an annual timeline, it means that honey bees will grow fast in the spring, enough to swarm in time for the resulting two colonies to now grow more foragers, to gather the resources necessary to survive the winter, and do it all over again the following year. Most beekeepers will manipulate the colonies at this time so that they can take advantage of these biological and environmental urges to reproduce.

The Beekeepers’ Spring Workload

When colonies leave the almond orchard at the end of February, they are destined to: 1) be split or broken down into multiple smaller colonies, effectively preventing swarming and increasing colony numbers, and 2) transfer bulk bees into packages to be sold across the country and make cell builders to raise queen cells and queens.

Splitting Colonies

Most beekeepers benefit from the early spring boost in colony buildup to split their colonies. They use these smaller units, or “splits” to increase their colony numbers, to either make up for last year’s loss and/or put more units into producing honey or participate in subsequent pollination events.

The process of splitting consists of going through each colony thoroughly and assessing each component for a fair division of resources. Beekeepers use different techniques and methods to split their colonies but the basic concepts are similar for everyone.

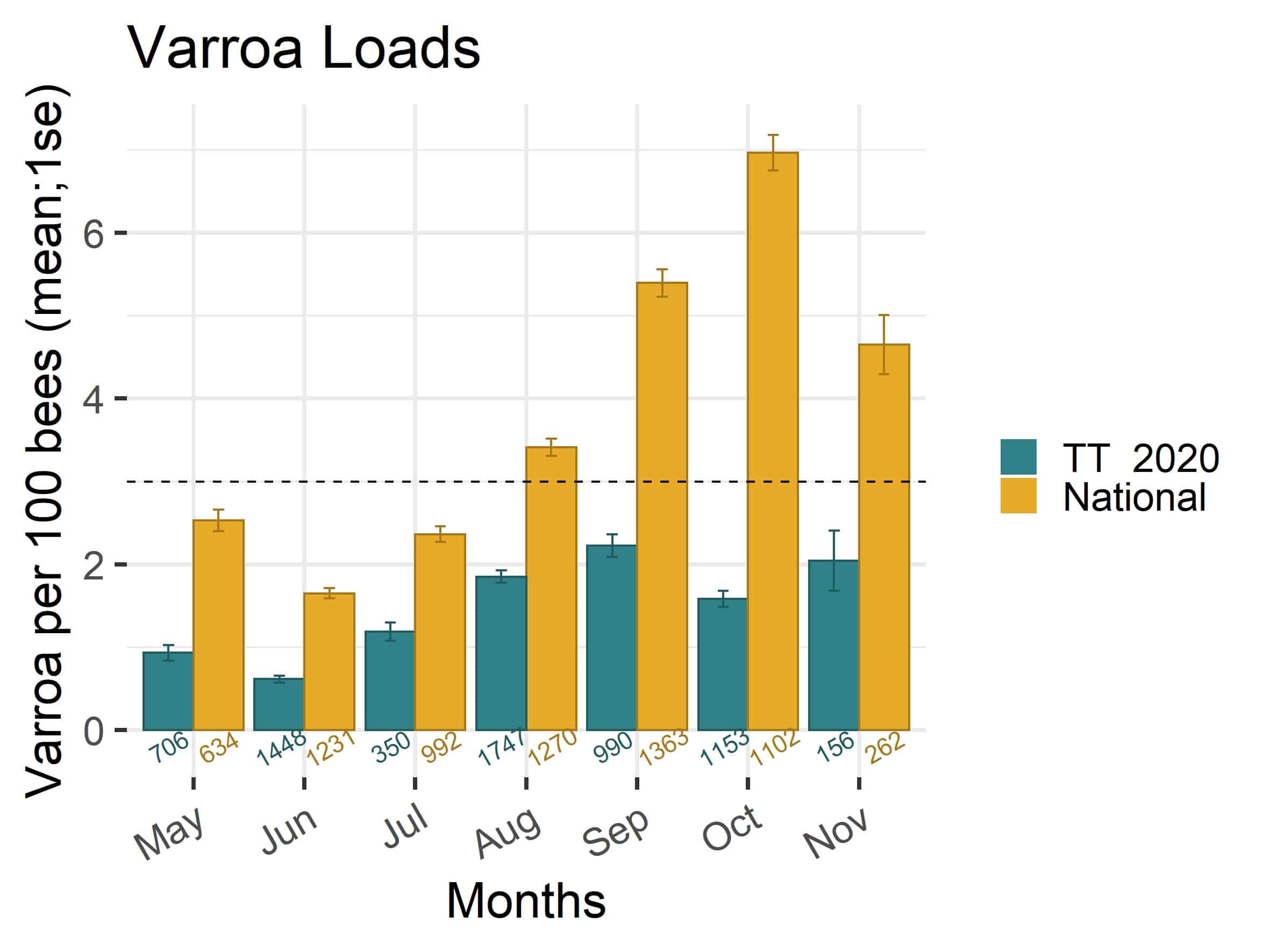

This splitting period presents a good opportunity to treat for pests and diseases, notably Varroa, in hopes of creating strong and healthy honey producing or pollination units. This is an important time for the Bee Informed Partnership to perform colony assessment and sampling for beekeepers, reporting back on the status of the operation, the trends from other colonies in the area, the effectiveness of early treatments and suggest actions to increase the strength of colonies going into production.

Making packaged bees and cell builders

The boost in colony population size during almond pollination also offers beekeepers the opportunity to use their excess bees to make packages to sell to all types of beekeepers across the US. The timing of such spring buildup of bees after almonds and the subsequent package production comes at a perfect time when the rest of the country is in need of new colonies to replace those they lost over the winter. Each package of bees weighs between three to five pounds, containing approximately 7,000–12,000 bees and a caged-queen. These packages will be installed in hive equipment and hopefully start a new colony. In conversations with package producers, some report the bee industry produces and sells over 250,000 packages to the beekeeping community each year.

Producing Queens

The queens need to be produced during this same window of opportunity. Beekeepers use excess bees to create what they call cell builders—(often) queenless colonies with a lot of young “nurse” bees and the necessary resources to produce numerous queen cells. Some queen cells are sold prior to hatching and used by many beekeepers to speed up the splitting process by introducing queen cells into their newly made units. Other queens will be allowed to hatch and mate before being sold either with bee packages or individually to beekeepers as sold as replacement queens that are mated and ready to begin laying eggs.

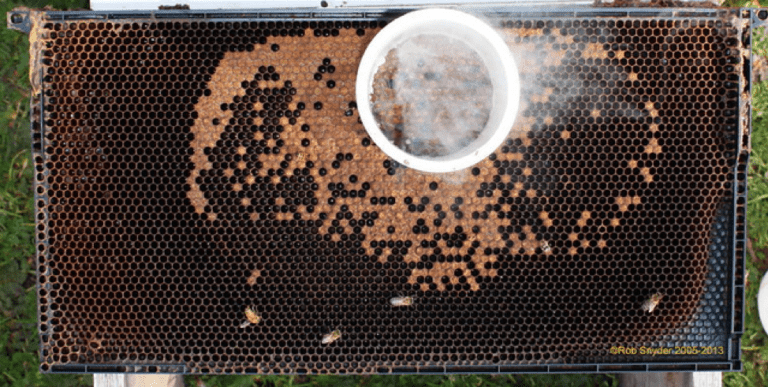

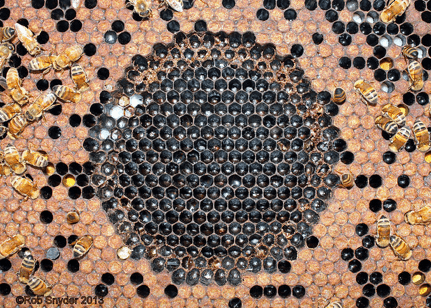

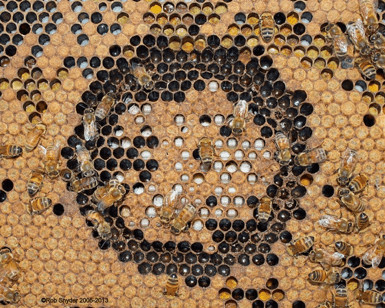

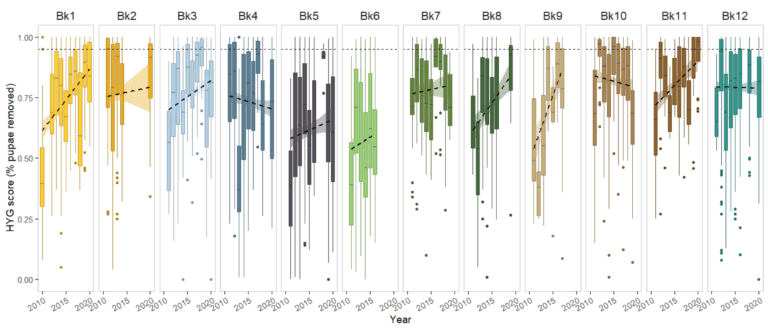

The Bee Informed Partnership works closely with many California Queen breeders during this period to assess colony health and sample for pests and diseases. Additionally, BIP performs testing on breeder queen colonies to measure hygienic behavior, a genetic trait that translates into better resistance against certain honey bee diseases. This hygienic behavior is the ability of worker honey bees to efficiently ‘sense’ diseased pupae, uncap them and remove them from the nest. The test consists of freezing a section of the brood, effectively killing the progeny, and counting the number of pupae removed in a 24-hour period. Those colonies with higher removal rates are considered more hygienic, and are thus more preferable to breed from than those colonies with lower removal scores.

BIP has played an important role in testing, reporting and advising California Queen Producers over the past decade, supporting them in selecting better breeding stock year after year. This is made evident by the statistically positive increase in hygienic behavior scores of bees from the BIP Tech Transfer Team Program participants, as seen in the graph below.

The marathon stretches on into summer…

Beekeepers often spend the months of March and April in a clement (southern) location, working at moving bees at night and splitting bees during the day. Once the splits have been made, the queens have been reared, the packages have been shipped and the weather warms up in the North providing food for the bees, beekeepers will pack up all their colonies and move them back to summer pastures for honey production and other pollination events. This time of year is a true test of the beekeepers’ strength, resilience and stamina.